Follow Erik Loomis on Twitter

Historian Erik Loomis on this day in labor history: July 23, 1892.

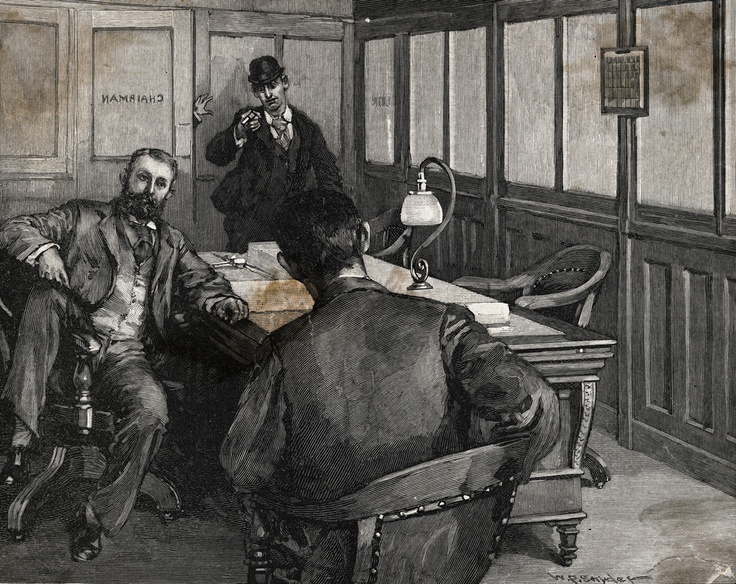

The anarchist Alexander Berkman walked into the office of Carnegie Steel executive Henry Clay Frick with a knife and gun in order to kill him for his actions at the Homestead Strike. Being an anarchist, he failed miserably.

Let’s start with a basic fact: Henry Clay Frick deserved to be murdered.

This was a truly awful human being responsible for the deaths of a whole lot of people. First, there was his culpability in the Johnstown Flood, where the negligence of he and his friends led to over 2200 dead people.

Admittedly, he didn’t order their killings, but he also just didn’t care whether they lived or died.

Second, there was his actions at Homestead. To review this famous incident, Frick was the second in command to Andrew Carnegie at Carnegie Steel. Frick hated unions. I mean, all Gilded Age capitalists hated unions but Frick truly despised them.

He once personally evicted a worker from company housing by picking him up and throwing him in a creek. The world would have been better off without Henry Clay Frick in it. But that doesn’t excuse Berkman’s actions.

Berkman was born in 1870 in Vilinus, in what is today Lithuania, to a wealthy Jewish family. Because of their wealth, the Czar allowed them to move from the Pale of Settlement to St. Petersburg.

The young Berkman became attracted to the radical political ideas part of the atmosphere there, which had famously led to the assassination of Alexander II. With his family increasingly ashamed of his radicalism, Berkman immigrated to the United States in 1888.

He immediately became involved in the fight to free the remaining Haymarket martyrs and joined the first Jewish anarchist group in New York.

He met another young Jewish anarchist, Emma Goldman, in 1889. They became lovers.

They also fell under the influence of Johann Most, the anarchist articulating “the propaganda of the deed,” which meant that individual acts of violence were good, even if they killed innocents, because the repressive state response would spark a revolutionary movement.

Berkman and Goldman moved to Worcester and opened an ice cream shop. Then Homestead happened. Although they had no connection to the steel workers, they decided that action was necessary to make Frick pay for what he had done. So they decided to kill him.

Goldman attempted to fund it by working as a prostitute, to ridiculous results.

https://www.lawyersgunsmoneyblog.com/2017/06/erik-visits-american-grave-part-86

But Berkman managed to get his assassination attempt in anyway. He wanted to make a bomb, because that’s how Russian anarchists rolled, but he didn’t know how. So he got a knife and gun.

He managed to get into Frick’s office. He fired two bullets at him and missed, because he was an incompetent clod. He was then tackled but managed to stab Frick three times.

But Frick did not suffer serious wounds. An associate of Berkman and Goldman’s named Modest Aronstam arrived in Pittsburgh the next day with dynamite to finish the job, but he was already known and when his name appeared in newspapers, he fled.

Let’s step back a moment and look at the ridiculousness of this act. It would be one thing if the Homestead strikers themselves decided to kill Frick. One could almost justify it. It wouldn’t have been the first time Gilded Age strikers used violence to defend their interests.

The Molly Maguires, while not really a labor movement per se, had done this.

Some anarchist threw the bomb at Haymarket, and while it was certainly not a member of the McCormick workers union who cops had killed the previous day, it was at least someone involved in the larger maelstrom of the Chicago 8-hour day strikes.

The miners at the Frisco Mill in Idaho had bombed a mine in a pitched battle with Pinkertons. In 1910, two Ironworkers leaders would blow up the Los Angeles Times building because Harrison Gray Otis was so critical to that city’s anti-unionism.

The latter ended up a complete disaster and was a bad idea to begin with, but at least in all these cases, it was the affected workers acting.

And then at Blair Mountain, West Virginia miners rose up in armed revolt against their oppression, leading to the largest domestic insurrection since the Civil War.

Berkman and Goldman were acting out of pure ideology. They didn’t know any Homestead workers and they didn’t consult with any Homestead workers.

Moreover, the attempted assassination turned public sympathy away from the strikers, who of course had nothing to do with it. Even Johann Most repudiated Berkman for this, embittering him. All Berkman’s actions accomplished was 14 years in prison.

He got out in 1906 and still worked with Goldman, even though their romance was dead. He suffered from crippling depression in his post-prison years. Finally, in 1907, Goldman named him editor of her paper, Mother Earth, and this gave him more purpose.

Berkman learned nothing. He was involved in a plot to build bombs after the Ludlow Massacre, again totally disconnected from the mineworkers. But one went off in the apartment where they were being built and most of his co-conspirators died.

Both Berkman and Goldman were rounded up and deported to the Soviet Union during the Red Scare. They both became disillusioned as well, but found themselves isolated by the left which had largely turned toward seeing the Soviet experiment as the future.

Berkman moved to France in 1925 and lived there until 1936, when he committed suicide because his health was failing badly.

He still didn’t know how to use a gun. He missed his heart and instead lingered on, unable to speak, for a while before slowly dying.

It’s also worth noting that for all their fame, not only did Berkman really accomplish nothing but to be honest, Goldman didn’t either.

They never connected with actual workers movements, nor did they become involved in the IWW, which certainly welcomed leading anarchists as organizers and propagandists.

They were independent operators and are massively overrated as historical figures, especially Goldman, who used her fame to give speaking tours that made her a good bit of money and avoided the hard work of organizing.

I’m not really taking a shot at Goldman here–but it is worth noting that in a life where there were always big time worker movements taking place, she played a key role in…none of them. As opposed to Mother Jones or Elizabeth Gurley Flynn or Clara Lemlich.

Frick would go on to be the most publicly hated man of the Gilded Age.

This was hardly the last moment of anti-employer or anti-capitalist violence during the Gilded Age. Most famous was Leon Czolgosz’s assassination of President William McKinley. Czolgosz made Berkman look rational and sane.

Eventually, all this violence did lead the government to begin wondering why and discovering that, yes, workers did have it horrible. But none of these acts caused anything close to the revolution that Berkman wanted to spark.