Follow Erik Loomis on Twitter

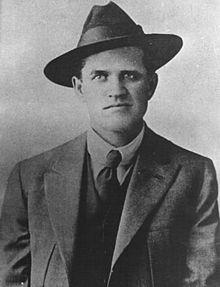

Historian Erik Loomis on This Day in Labor History: August 1, 1917. The IWW organizer Frank Little is lynched in Butte, Montana. Let’s talk about this horrible but famous incident!

His murder, one of the most famous killings of a labor organizer in American history, demonstrated the lengths to which mining companies were willing to go to keep their company towns under control.

Frank Little was born in 1879, a mixed race son of a white father and Cherokee mother. We know little about his early life, hardly an uncommon situation for a poor person. Little joined the IWW in 1906. He traveled the nation organizing workers in many of the IWW’s key actions.

He was deeply involved in the IWW free speech campaigns in Missoula, Spokane, and Fresno. He organized the lumberjacks of the Pacific Northwest, the miners of Minnesota, fruit pickers in California’s San Joaquin Valley, and the oil field workers of Oklahoma.

Little rose fast in the IWW. In 1916, he was named to the IWW Executive Board, having gained the trust of IWW leader Big Bill Haywood.

Butte was controlled by the Anaconda Mining Company. One of the most powerful corporations in American history, Anaconda basically controlled Montana by 1917. It produced 10% of the world’s copper. It also hated unions.

In the late 19th century, Butte was arguably the nation’s strongest union town, known as the “Gibraltar of Unionism” for its closed shop. But in 1903, Anaconda completely crushed the union and ran Butte with an iron hand from then on.

After 1912, no one could work in the Butte mines without the rustling card, effectively a permit granted to individual workers by Anaconda. It used this card to drive out anyone suspected of union organizing.

While Butte miners were strong AFL members during their heyday, the post-1903 situation was precisely the kind of thing the Industrial Workers of the World looked for: desperate yet proud workers who could be roused toward radical action.

And by 1917, Butte workers were ready to strike. In June, a fire in the Speculator Mine, actually not owned by Anaconda, killed 164 miners, the worst hard-rock mining disaster in American history. Workers walked out in a spontaneous strike.

Now, this was still not a radical hotbed. Workers struck, but they weren’t necessarily looking for the IWW.

They formed the Metal Mine Workers Union, demanding the end of the rustling card, collective bargaining rights, observance of state mining laws, free speech rights, discharge of the state mine inspector, and a wage increase.

This soon expanded into new demands for safety instruction for miners and construction of manholes in the mines. By June 29, 15,000 men were off the job.

The companies responded by blaming the IWW (which was not involved as an organization at this point, although there were maybe 500 Wobbly members in town at the time) and indicted the workers for radicalism and pro-German sympathies during World War I.

On July 18, Little arrived. He was on crutches, after having hurt himself in an accident organizing miners in Bisbee, just before the famed Bisbee Deportation, where mining companies rounded up over 1100 other workers and dropped them in the middle of the New Mexico desert.

Not yet recovered, he boarded a train for Butte, his final destination. Little’s arrival and especially his outspoken opposition to World War I threw the mining companies into a frothy fury.

They reprinted his anti-war speeches and accused him of promoting revolutionary and pro-German beliefs in the middle of an industry necessary for wartime production. Spies reported Little calling for revolution during union meetings.

The truth of this is impossible to ascertain given that the spies had incentive to report things like this, but given Little’s fervor, it’s possible. In any case, the companies were inclined to believe the most incendiary reports about Little.

Little’s allies told him to get out of town. He wasn’t very successful at organizing in Butte and the calls for his murder were very real. But he refused. It seems that he perhaps had come to terms with the possibility of martyrdom.

On August 1, six masked men came to his hotel room. They tied him up, took him to the edge of town, beat him, and hanged him from a railroad trestle. On his chest they pinned a note that read “3-7-77,” a code used by the local vigilante committee to take credit for the murder.

A few days after Little’s lynching, Montana declared martial law against war opponents, rounded up radicals of all stripes, and engaged in a massive state-sponsored violation of civil liberties.

3,000 people marched at Little’s funeral. The funeral was filmed and shown around the country. Other strike leaders tried to rally labor around Little’s lynching. But in the end, Anaconda won the struggle.

On August 10, U.S. troops arrived to “protect” the mine from radical agitation, but in fact they were used as a strikebreaking force. The strike itself was never all that strong.

The unions outside the mines that had walked off were offered better contracts and quickly accepted them, leaving the miners isolated even before Little’s murder. The strike collapsed, although the IWW remained active in Butte until 1920.

Two weeks after his murder, governors of northwestern states met in Portland to discuss a coordinated response to IWW agitation, which would lead to massive violations of civil liberties and murders of unionists over the next three years, including at Everett and Centralia.

No one was prosecuted for Little’s murder. Even today, we aren’t sure who precisely did it, although there’s no question it was interests close to Anaconda. He was buried in Butte.