Follow Erik Loomis on Twitter

Historian Erik Loomis on This Day in Labor History: August 2, 1995. California agents raided an apartment complex in El Monte, California, freeing 72 Thai immigrants forced to work in an illegal sweatshop. This case demonstrated the labor trafficking that still goes on in the United States, even today!

The American sweatshop in the popular mind is something of the late 19th and early 20th century east coast city.

Starting with the home production of low-skilled trades such as the artificial flower industry, it became a hallmark of the needle trades, first in individual homes and then in the larger factory sweatshop that garnered public attention in the Triangle Fire.

The outrage over Triangle and the reforms that followed, combined with the growth of the unions in the 1930s and the mid-century factory made sweated labor less of a big deal for much of the later twentieth century.

But the arrival of a new wave of immigration following the Immigration Act of 1965 and the decline of the unionized factory opened up new opportunities for people who wanted to exploit the poorest possible people.

In 1988, a Thai family in the U.S. decided to start their own sweatshop in California. Led by a woman named Suni Manasurangkun and her children and their spouses, they started canvassing rural Thailand, looking for workers.

The power of going to America was very appealing for these impoverished people. They talked a lot of big words to these poor people. They dressed them in expensive jewelry for the flight over so they wouldn’t have any problems getting through immigration.

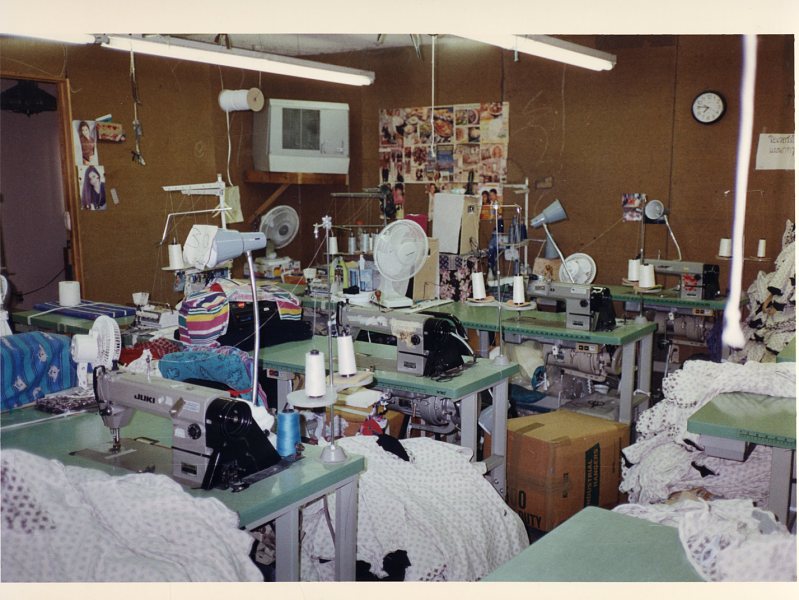

Then, once they left the airport, they were turned into slaves. Their passports and money were stolen. They were taken to the complex in El Monte, outside of Los Angeles, which was surrounded by razor wire.

Guards armed with knives and baseball bats made sure that workers did not try to escape. One did try and was beaten severely. The guards routinely showed pictures of that guy to intimidate the workers.

The workers often worked 17 hours a day and at times up to 22, which does not seem possible but is nevertheless true.

They were forced to buy products at the company store at inflated prices, an old tactic of employers with full control over employees to take back the limited wages they paid.

But in this case, without actually paying wages, it was all just added to the debt that the women would never be able to pay back.

Of course, clothing retailers intentionally knew nothing about what was happening. This remains an intentional position by the industry today.

From Triangle to the present, the department stores and clothing companies have controlled for cost and quality but have taken no interest in the conditions of labor.

This has incentivized the worst possible labor conditions. The El Monte sweatshop’s clients included then clothing lines Anchor Blue, B.U.M., High Sierra, CLEO, and Tomato Inc.

It turned out that the razor wire was not initially outside the factory. But early in the sweatshop’s history, one worker actually had escaped, leading Manasurangkun to put up the added security.

That worker was heavily traumatized and told no one the story but her boyfriend and then, later, a coworker. In 1995, that woman and her boyfriend were working at another, legal, clothing factory.

An inspector with the state of California named TK Kim was in that factory and that coworker repeated the story to him. Alarmed, he interviewed the escaped woman and she gave up the information. Kim and the state did this the right way.

They went to the Thai community for help. Working with the Thai Community Development Center, the state asked if the community would participate in a raid on the sweatshop. It agreed.

On August 2, 1995, the State of California Labor Commission, the United States Department of Labor, the United States Marshals, the California Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the State of California Employment Development Department, the El Monte Police, raided.

The Thai Community Development Center’s role was speaking to the workers in Thai and telling them what was going on.

The raid exposed the horrible conditions in the sweatshop. But that does not mean that everything was now better for the workers. They faced a real threat of deportation.

They went under Immigration and Naturalization Service custody and were locked up in their detention facilities. But the TCDC and their allies in the Asian-American community demanded that they be allowed access to the workers.

After nine days, the workers were transferred to TCDC custody.

The Union of Needletrades, Industrial, and Textile Employees (UNITE), a fading union that was the descendant of the old needle trade days, also demanded that the workers be allowed freedom based on signature bonds rather than cash bonds, as obviously that was impossible for them.

Finally, an INS lawyer creatively used the S Visa, known primarily for its use to keep people who busted open drug cartels in the country, for these workers, allowing them to establish legal residence with three years in the country.

As the workers would have been in danger returning to Thailand, this worked out.

A civil suit against the companies who didn’t care about the conditions of work in the making of their clothing netted the workers $3.7 million. Not that much, really.

In February 1996, the eight El Monte operators, Suni Manasurangkun and her family, pleaded guilty to conspiracy, involuntary servitude, and smuggling and harboring of illegal immigrants. They received federal prison terms from between two and seven years, followed by deportation.

The El Monte incident led to a lot of attention on Asian-operated sweatshops in the Los Angeles area, as impoverished people attempt to create a better life for themselves and are lured into involuntary servitude.

The Clinton administration created a sweatshop task force. But it remains a big problem today, as does the sweatshop issue globally. Companies continue to not care about the conditions in which their goods are created.