Follow Erik Loomis on Twitter

Historian Erik Loomis on This Day in Labor History: August 4, 1942. The United States and Mexico made an agreement to deliver contract Mexican labor to American farmers in order to serve as cheap replacement labor during World War II. Let’s talk about the Bracero Program and abuse of Mexican labor!

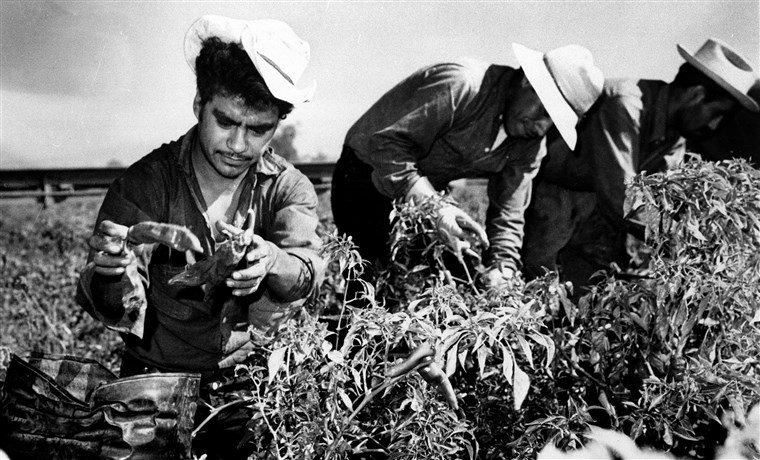

Mexican-Americans made up an important part of the agricultural labor force in the Southwest long before World War II.

While most of the land the U.S. stole during the Mexican War was not densely inhabited, Mexicans in California, Texas, and especially New Mexico found themselves all of a sudden second-class citizens in their new nation.

Agricultural labor was all many could find within the white supremacist economy of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Moreover, the upheaval of the Mexican Revolution sent waves of Mexicans across the U.S. border for the first time in the 1910s.

That was great for American farmers who wanted to pay their labor as little as possible. It also gave them an alternative to the white labor that tended to join the IWW and demand decent pay and living conditions.

But during the 1930s, as whites needed jobs, any job held by a non-white was seen as a betrayal of white supremacy.

John Steinbeck may have movingly told the story of white migrants to the California fields in The Grapes of Wrath, but he almost totally leaves out the history of Mexican labor in those same fields. During the Great Depression, that labor was forcibly expelled from the Southwest.

During the 1930s, over 500,000 Mexicans returned to Mexico, many by force through deportation, others by social pressures. Whites took their jobs.

But during World War II, what seemed like good social policy to many whites turned into a disaster because all of a sudden white people could make a lot more money than they could in the fields.

So U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt and Mexican President Manuel Avila Camacho agreed to the Bracero Program. Essentially, this provided Mexican labor to American employers through short-term contracts.

When the contract ended, the worker returned to Mexico. Crops are picked, America stays white. By 1945, about 125,000 Mexicans worked under Bracero contracts, not only in agriculture, but for the railroads.

Originally the program was to end in 1947 and the railroad program concluded upon the return of soldiers in 1945.

But southwestern farmers, who, due to their power within their relevant states and long distances from the centers of national power, managed yet again to convince the otherwise pro-labor federal government of the New Deal era to facilitate their exploitation of workers.

Farmers’ exemption from complying with the Wagner Act and the Fair Labor Standards Acts are other examples of this. By 1956, 456,000 Mexicans labored in the fields under Bracero contracts.

Under these contracts, workers effectively had no rights at all. Because they could be employed legally nowhere besides the fields, they worked in near slave conditions. Contracts were only in English and the Mexicans had no idea what they were signing.

Wages were stolen, housing was substandard if even provided, food was terrible, and complaints resolved by sending workers back to Mexico.

In fact, there was so much racist violence against Braceros in Texas that Mexico suspended the program in that state.

Here’s one remembrance of conditions from Rigoberto Garcia Perez: “In Tracy I was with a crew from Juajuapa de Leon, in Oaxaca, and one of those boys died. Something he ate at dinner in the camp wasn’t any good. The kid got food poisoning, but what could we do? We were all worried because he’d died, and what happened to him could happen to any of us. They said they’d left soap on the plates, or something had happened with the dinner, because lots of others got diarrhea. I got diarrhea too. But this boy died.”

It was these sorts of conditions, the everyday exploitation of Mexican labor, that helped motivate the Chicano rights movement in the United States.

The United Farm Workers built off the treatment of Mexican and Mexican-American labor like that Garcia Perez experienced to create its movement to improve working conditions in the fields.

The Bracero Program ended in 1964. Two things replaced it. First, the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 provided a legal pathway for immigrants to enter the U.S. for the first time since 1924, although for Mexicans obviously this was a more complex legacy.

Second was the establishment of the Border Industrialization Program in 1965. BIP was intended to keep Mexican labor south of the Rio Grande by giving incentives to American companies to cross the river and use cheap Mexican labor.

While capital fled to Mexico, neither increased legal immigration nor BIP came close to filling the employment needs of Mexicans driven from their traditional lands by a complex cluster of factors.

Undocumented migration to the United States grew rapidly in coming decades. This new phase of immigration continued the history of exploitation of Mexican workers by American employers.