Follow Dave McKenna on Twitter

Something I’ve learned while in law school is about the social construction of crime.

I work in a legal clinic on wage theft cases, where employers have “improperly paid” workers by not paying, paying below minimum wage, withholding overtime, paid sick time, etc.

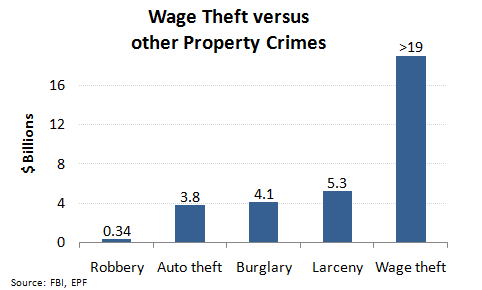

Most theft is wage theft. Meaning, the dollar value of stolen wages is greater than the value, each year, of all burglaries plus robberies, shoplifting, auto theft, combined.

Yet, wage theft is NOT A CRIME!

If you steal $100 from your employer, you will get arrested. If you call the police because your paycheck is $100 short, the police will tell you to file a complaint with the Attorney General, and the Attorney General will settle the case for between $50 and $200.

That’s actually not true, because Attorney Generals only take on big cases where thousands of dollars are at stake. But they will settle big cases by typically requiring the employer to properly pay what is owed. No jail, no criminal record.

If the Attorney General doesn’t want to take the case, it will give you a Private Right of Action to sue the employer in civil court for what you are owed, plus damages. It can take six to eighteen months to win at trial, and months or years to collect on the judgment IF you win.

In short, we address the predominant form of theft in the US with civil court cases, not criminal cases. We have literally defined “wage theft” as not a crime. Theft by you? A crime. Theft by your employer? Not a crime.

This is what we mean when we say crime is “socially constructed.” Not all social harms are criminalized. Not all actors committing social harm are criminalized.

I settled a case for $27,000 for three clients last year. We spent a MONTH negotiating the non-disclosure agreement because the employer stated if all his employees sued him and settled like this, he would go BANKRUPT. His business model DEPENDED on wage theft.

These employers go on to hold elected office. President Trump famously used wage theft to improve his finances on construction projects, leaving a trail of victims in his wake. Some sued and he had to pay them. Others didn’t have resources to pursue multi-year litigation and got nothing.

Wage theft shows that we believe restitution is important. Giving the money back is important. Currently, the Attorney General keeps track of bad actors and will increase future financial penalties for bad actors.

It also shows when harm is committed, we don’t have to lock someone in a cage or label them a felon — both of which destroy years of life even after the sentence is over. We can demand restitution instead of punishment.

It also shows how ridiculous the label “high crime neighborhood” is. And the arbitrary and racist response of police surveillance in “high crime neighborhoods.” Because we defined it that way.

Consider the social construction of murder.

Poison a person, you go to jail, and they call you a felon for life. Poison a city resulting in dozens of deaths and thousands with brain damage, you get a teaching fellowship at Harvard, and they call you ex-Governor of Michigan Rick Snyder. Same with much corporate poisoning.

The people committing the most harm aren’t in jail, and don’t live in “high crime neighborhoods.” And “black people commit more crime” is true only because of how we have defined crimes, and how we then surveil their communities in order to find more crimes.

In the employment context, we can prevent wage theft by replacing corporate ownership with employee ownership: worker owned cooperatives that share profits and losses, removing the power dynamic that incentivizes wage theft in the first place.

Power corrupts.