Follow Erik Loomis on Twitter

Read Erik Loomis on Lawyers, Guns, & Money

Historian Erik Loomis on This Day in Labor History: August 26, 1922. The Trade Union Educational League under the leadership of William Z. Foster publicly met for the first time. Let’s talk about this early attempt to bring communism into the labor movement.

The pre-1917 labor movement had a panoply of radicalism in its ranks. Of course, many workers were not radical at all.

But those who were ranged between all sorts of ideas. Anarchism and syndicalism were major parts of the labor movement, with the IWW the semi-institutional representation of the latter.

Socialism in its many forms was in the ascendant, both in terms of the work of Eugene Debs and many other ideas and movements. What was less dominant was communism per se.

That didn’t really take off until after the success of the Bolsheviks. But once that did — especially in the context of the Red Scare decimating the IWW and deporting many immigrant radicals such as Emma Goldman — communism began to take over the left-wing of the labor movement.

No single individual did more to make this happen than William Z. Foster. He had been a socialist since 1901 and worked for the IWW for quite a while. He became a strong syndicalist after visiting Europe for conferences with other radicals in 1910-11.

He broke with the IWW and attempted to start his own pure anarchist-syndicalist movement, but — not surprisingly — it flopped. He switched his organizing strategy to infiltrating existing unions.

He took a job as a business agent for the Brotherhood of Railway Carmen and then as a general organizer for the American Federation of Labor in 1915, even as he worked toward syndicalism outside his job.

Foster plunging into the heart of the labor movement did lead to political compromises. He did not publicly oppose World War I or criticize the mass arrest of IWW members during the war, which the AFL officially cheered.

Foster instead got involved in organizing the meatpacking houses of Chicago, creating the Stockyards Labor Council, an industrial union structure intending to organize all the workers within the guise of the preexisting unions, which were mostly skilled labor organizations.

But — as these unions excluded African-Americans from membership — the factories simply hired thousands of recent black migrants from the South.

Once again, racism got in the way of class solidarity, again showing why supposed “class not race” beliefs are in fact racist. Race consistently got in the way of organizing and the SLC was dead by 1922.

Foster then played a critical role in the 1919 steel strike — one of the largest and most important of the post-World War I strikes. Despite the AFL showing indifference, Foster and his organizers signed up over 100,000 steel workers by 1919 and in August 250,000 workers went on strike.

When the military crushed the strike, Foster continued his journey outside the AFL. The Communists were suspicious of Foster when he joined up; after all, he had been all over the place within the labor movement. But he proved an effective organizer.

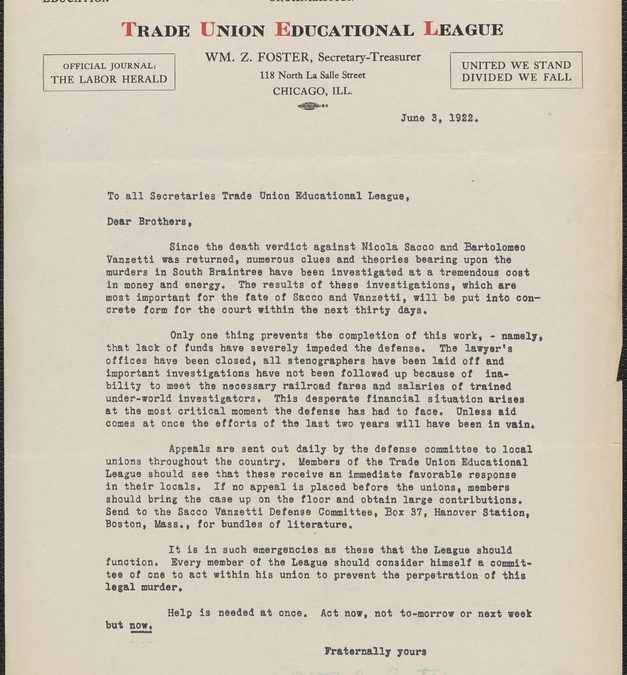

The Trade Union Educational League was Foster’s big idea to bring communism into the American labor movement.

This was not a thing that was much more than an idea when he and a few other unionists had a private meeting in 1920 to push it forward, with some money from the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, which had a strong socialist bent.

Foster visited the Soviet Union after this meeting and became a convert to the Communist Party and its methods. He came back to the U.S. and became a propagandist for the Soviets, raising money from famine relief and writing about his experiences there.

The TUEL’s goal was to organize within the labor movement to turn existing unions into communist-led unions using the discontent that many workers have long felt toward their union leaders.

Foster immediately had strong enemies — especially an aging Samuel Gompers — who despised the left and had gladly worked with the Woodrow Wilson administration to destroy the IWW, suddenly finding itself with a new threat.

He also faced another expected enemy — the cops. Police raided the first public conference for the TUEL, in Chicago that began this date in 1922. It was the second day of the conference.

Cops found a reason to arrest 15 people, including Earl Browder, but the conference went on. Foster noted about the overall condition of unionized workers by this time and the need for a new approach, “In the days when the unions still possessed some militancy, the conditions of organized workers always stood forth clearly as being far better than those of unorganized workers. But now in many cases union workers are employed under conditions little better than those of non-union workers. This is a deadly situation.”

The TUEL worked to burrow from within unions. It published a series of magazines based on industry to propagandize the respective workers. The Industrialist was dedicated to the printing industry, The Railroad Amalgamation Advocate for that industry, etc.

The TUEL tried to take over the United Mine Workers of America in 1922 and 1923, building on a leftist challenge that was a real movement in several states and even in British Columbia.

But these rebels were going up against the dictatorial John L. Lewis and his response was simply to expel everyone associated with it from the union.

The TUEL also alienated progressive labor leaders such as Sidney Hillman, who denounced it as dual unionism and suspended its leaders within his Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America.

That was a big loss, as the ACWA had long supported Foster. But the TUEL did take the lead in a number of textile strikes in the Northeast between 1926 and 1928.

The 1920s and 1930s was a period of rapid change for communists, both inside and outside the Soviet Union. Strategies were transformed seemingly overnight. In 1928, the communists decided that Foster’s strategy of boring from within unions was not working.

It closed the TUEL and started the Trade Union Unity League, a series of industrial-based communist unions to openly challenge the established unions.

Foster found himself out of fashion and although he remained committed to the cause, spent most of the rest of his life engaging in internal communist infighting — usually losing.

But he remained a strong communist following the line from Moscow for the rest of his life, including when Khrushchev denounced Stalin in 1956. In fact, Foster died there in 1961.

The Trade Union Educational League didn’t accomplish a whole lot, but it was an earnest and important attempt to move the traditionally conservative American trade union to the left and had a big influence on the communists that would do critical work in creating the industrial unionism that would transform the nation in the 1930s and 1940s.