Follow Erik Loomis on Twitter

Historian Erik Loomis on This Day in Labor History: July 20, 1891. Militia forces guarding a stockade at a mine near Briceville, Tennessee surrendered to miners during the Coal Creek War to keep convict laborers from competing with free miners. Let’s talk about how prison labor is used to undermine workers!

After southern treason in defense of slavery was crushed, not only was the southern elite stripped of their capital, but the states themselves were a physical and financial wreck, often run through over and over again by four years of battles and marches.

Such was the case in Tennessee. Other than Virginia, no southern state suffered more damage. The state had no money. But the Reconstruction government there did have prisoners.

Without the ability to even pay to keep prisoners, in 1866, Tennessee began renting their convicts out to coal companies in exchange for the companies paying for their board.

The irony of unpaid prison labor in the wake of the Thirteenth Amendment is rich, but that amendment did make an exception for prisoners and that loophole has been blown wide open ever since as prison activists can tell you.

Tennessee was not the only state that did this.

For instance, in 1866, Virginia’s prisons began a similar program for railroad companies and among the convicts sent to his death this way was a young black soldier from New Jersey railroaded into prison named John Henry, who would become a mythical legend in American culture.

By 1871, Tennessee was leasing its convicts to the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railway Company (TCI), which subcontracted the prisoners to small coal mines.

This immediately created dissatisfaction from free laboring coal miners, but there was not too much organized action against it in the early years.

During the 1870s, Coal Creek, in Anderson County, on the Cumberland Plateau, became the state’s coal center. By the 1880s, miners, locked out of the profits the coal companies raked in on their unfree labor, began seriously organizing.

Ultimately, it was the rise of the Farmers’ Alliance, the state organizations that would lead to the Populist Party, that gave miners the organization they needed to resist unfree competition.

The Tennessee Farmers Alliance and their allies in the fading but still locally relevant Knights of Labor elected several supporters to the state legislature, as well as a new governor.

Feeling emboldened, it next made direct demands on the coal mines, including the end of the use of company scrip and that miners could use their own checkweighmen, which were the people who weighed the coal and determined how much the miner would get paid.

In fact, both of these things were already mandated by state law but ignored by the owners.

In the face of new pressure, most agreed, but the Tennessee Coal Mining Company, operating a mine on Coal Creek, near Briceville, refused and moreover, tried to force miners to sign a locked-in 2 year contract that gave them none of these things.

When they refused, TCMC shut the mine and reopened it on July 5 with state prisoners contracted through TCI. It then tore down company housing, kicking out residents, to build a new stockade for the convict laborers.

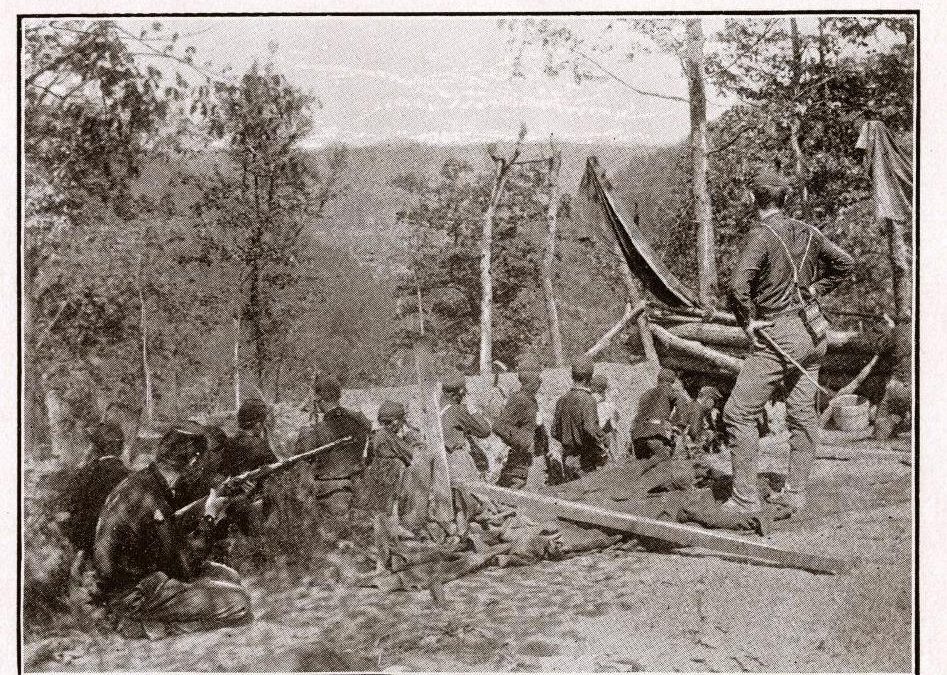

This led to an explosion of anger. On the evening of July 14, fearing more convict laborers, miners and other concerned locals met and decided to do something about it.

The next evening, a group of 300 armed miners marched to the stockade, probably led by local Knights of Labor members, took it over, and placed the prisoners on trains to Knoxville.

They hoped their newly elected governor, John Buchanan, would support their action based on their own version of private property rights–they were defending their wages and property from essentially enslaved people.

But Buchanan himself helped escort the prisoners back to Briceville, one of many examples of the Farmers Alliance, Populists, and unionists electing people to office during this era, only to have them turn on their working-class supporters when the opportunity to cash in came.

Shots were fired at the stockade that night and 100 militia members were left to guard the prisoners.

On the morning of July 20, 2,000 armed miners surrounded the stockade. Miners came all the way from Kentucky to help, as the convict miners had recently been evicted in that state and there was worry about the system returning.

The militia surrendered and once again, the convicts were loaded on a train back to Knoxville. Simply put, local miners would not accept unpaid competition.

This put greater pressure on Buchanan, who got the miners to back off with the promise of a legislative session to deal with the legality of convict labor. Little happened though and a state court ruled against the miners, placing the sanctity of contract over all.

Miners responded on October 31 by taking over TCMC and burning several buildings. The 300 prisoners in the stockade were freed, given clothing and food, and told to go somewhere else.

On November 2, another band of miners did the same at the stockade at Oliver Springs, freeing another 150 prisoners. Finally, the state dispatched armed militia to ensure the ability of TCMC to use convict laborers.

The militia were largely from west and middle Tennessee, and there was immediate tensions between the two sides, with plenty of shooting at each other.

But by this time, TCMC wanted to be done with the convict laborers, which had become more trouble than they were worth. The company came to an agreement with the miners to stop using the prisoners.

That said, TMI had no interest in stopping its contracting with mine companies for this profitable operation. It directly purchased a mine at Oliver Springs and sent the prisoners there. This led to another round of violent conflict.

Miners in Grundy County and Marion County tore and burned down stockades there. At Coal Creek, the militia head was captured and a direct charge on the militia led to the killing of 2, but the miners couldn’t take the stockade.

At this point, Buchanan ordered a militia company of 600 men to retake east Tennessee from the miners. This proved effective and hundreds of miners were jailed. Only one miner served any meaningful jail time as many fled and others were acquitted. Order was restored.

In the aftermath, Tennessee banned the convict lease system in 1896, making it one of the first southern states to do so

It didn’t do this because it opposed using unpaid labor, but because the cost of keeping the militia in the field was more than the money the state made on the prisoners.

The incident became part of Appalachian lore and was remembered in the region’s amazing music.