Follow Erik Loomis on Twitter

Read Erik Loomis at Lawyers, Guns, & Money

Historian Erik Loomis on This Day in Labor History: September 8, 1919. Workers return to work after victory in the Pressed Steel Car Company strike at McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania — a huge and unexpected victory for the American working class during this dark time of workplace repression.

The Pressed Steel Car Company was a factory owned by the capitalist Frank Norton Hoffstot in McKees Rocks, a town on the Ohio River a bit downstream from Pittsburgh.

It made steel railroad cars — both for passenger and freight trains — and it soon became the second largest producer of such cars in the country. The factory employed 6,000 workers, mostly immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, and it treated them like peons.

The working and living conditions were notoriously awful, even for the Gilded Age. This company and its managers simply did not see its workers as people.

Said Reverend A.F. Toner, a local priest, “Men are persecuted, robbed, and slaughtered, and their wives are abused in a manner worse than death—all to obtain or retain positions that barely keep starvation from the door.”

The local coroner estimated that about one person a day died in the factory. The company owned all the housing and did not pay enough for workers to actually pay for that housing in many cases.

So when the rent fell short, managers would demand sexual favors from the wives and daughters of the workers to make up for it. The use of company stores at inflated rates for basic supplies only increased the exploitation.

Even for the Gilded Age, this is scumbaggery beyond the norm.

Moreover, rather than just hire workers, Pressed Steel gave foremen total control over who worked and who didn’t. Foremen were given an amount of money and told to hire the men needed to do the job for that money. This was called “pooling.”

What this led to is the foreman requiring kickbacks from the workers for them to make any money at all. This absolutely infuriated the workers. It’s pretty bad when Homestead was a better option, but this is how bad Pressed Steel was. One journalist wrote of pooling:”President [Frank N.] Hoffstot says that it has proven to be a very satisfactory arrangement. And it has — for the company. As evidence of this we saw several pay envelopes showing that many of the workers slave for practically nothing. One envelope showed that the owner worked nine days, ten hours a day, and got $2.75; another eleven days and received $3.75; another three days and got $1.75; another four days and got $1, and the fifth, who had been idle for two months, worked three days and received nothing…. The company manages the pooling system through the foreman — and the workers are skinned until their bones shine. Two years ago, before the pooling system was introduced, the men were making $3, $4, and $5 a day. Today most of them make 50 and 75 cents and $1 a day.”

Finally, workers just snapped. On July 10, 1909 — which was payday — the checks were even smaller than usual. The managers didn’t even bother explaining it. The workers spontaneously decided to strike.

There was no pre-existing organization here. This was just sheer fury in force. The company fired 40 workers immediately, which set off even more anger. The company went straight for violence.

It hired Pearl Bergoff, one of the nation’s leading strikebreakers, trained by the infamous James Farley. Bergoff brought in mostly black strikebreakers from the South, without telling them what they were coming for.

Then, when they arrived, they were forced to live in a barn with up to 2,000 other men. The company didn’t bother feeding the strikebreakers for the two day rail trip to Pennsylvania. When they did get fed while strikebreaking, it was cabbage and bread.

They were stolen from, beaten, intimidated, and not allowed to go outside. The strikebreakers themselves began to organize and by August 28, two hundred of them had left and started a camp on the Ohio River.

They attempted to collect back wages, getting lots of attention because they named the local police chief and Pressed Steel executives by name in their own oppression. They later testified before Congress about their treatment.

When the strike began, the media was — as usual — against the strikers.

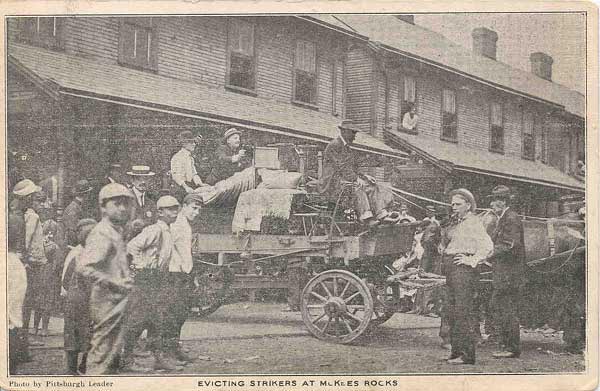

When the strikers were evicted from company housing, the New York Times reported, “The illiterate foreigners were like so many savages today when they first caught sight of the khaki-clad constabulary who had come in during the night.”

Classy.

Violence started quickly. An immigrant named Stephen Horvat was the first casualty, killed by an armed strikebreaker in one of those tragedies of the labor movement. No doubt the strikebreaker, an African-American named Major Smith, was scared to death himself.

But then race has always been used by capitalists to divide the working class, not that the working class itself wasn’t more than willing to be divided in that manner.

As the strike developed, organizers with the Industrial Workers of the World arrived to help organize it. As was often the case, workers themselves began actions and then the IWW would pop in to help out. This was the first major strike action in that union’s history.

Up to this point, it had primarily been involved in smaller actions and in internal divisions that had just recently been solved, allowing the organization to move forward with positive actions.

William Trautmann, one of the IWW’s founders, was the first major organizer, and when he was arrested, Joe Ettor arrived to replace him. Big Bill Haywood also arrived to rally the workers.

But in the end, this was a strike led by rank-and-file workers. Some of these were experienced organizers. A few had served in the 1905 Duma in Russia.

Others were Italian strike leaders who later immigrated to the U.S. 5,000 workers went on strike in McKees Rocks, and at least 3,000 more in Pressed Steel plants in Butler and New Castle.

The above photo — showing a deputy sheriff named Harry Exley putting a baby stroller on top of a wagon while evicting a striker — was printed in a Pittsburgh paper and then spread around the nation, building national support for the plight of these oppressed workers.

Then things got violent. At a checkpoint, a group of strikers identified Exley and started harassing him. That harassment turned into a mob of fury, as the people blamed Exley for much of their oppression, rightfully so, as he was an utter thug of the worst kind.

The mob grew and they killed Exley. That led the Pennsylvania State Police mounted on horseback to attack the strikers.

The workers were already calling that police force the “Black Cossacks,” reflecting how they connected the terror they felt in Pennsylvania to what they had felt back in Russia, where many workers originated. At least 16 people died that day. Martial law was declared the next day.

This should have led to the crushing of the strike entirely. But it did not. The national outrage over the violence overwhelmed the resistance of the company. Finally, the workers won.

On September 8, Pressed Car caved, gave a wage increase, posted standard wage rates, and stopped the exploitation in company housing.

Eugene Debs, who also assisted on the strike, called it, “The greatest labor fight in all my history in the labor movement.”

It didn’t lead to a new dawn of labor rights in the United States, but it was one of the most important victories of the early twentieth century and significantly improved the lives of the workers.

I’ve long been curious why this strike isn’t more famous on the left generally, up there with Homestead and Haymarket and Pullman, etc. But historical memory works in weird ways.