This Day in Labor History: July 5, 1935 — FDR signed the National Labor Relations Act

via Historian, Erik Loomis

“President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the National Labor Relations Act. This groundbreaking piece of legislation gave workers a fair shake from the government for the first time in American history.

When FDR took over the presidency in 1933, the economy was in the worst state in American history. But Roosevelt wanted to help business, not hurt it. His first New Deal labor legislation was really more a pro-business measure.

The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) intended to bring business on board with a reform program, and in fact parts of the act were welcomed by corporations — especially as it promoted bigness to undermine harmful competition.

Somewhat unintentionally, the NIRA’s provision protecting collective bargaining for workers was interpreted by American workers as giving them approval to strike.

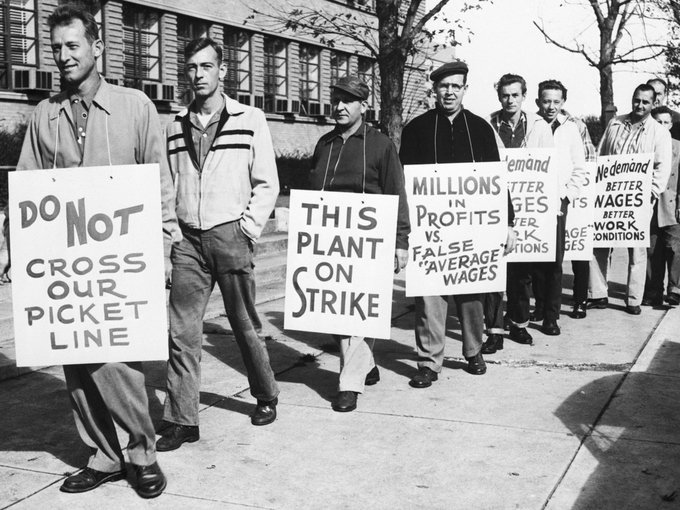

1934 saw some of the greatest militancy in American history, with major strikes in San Francisco, Minneapolis, Toledo, and the textile plants in New England and the South. This growing labor movement helped cleave corporate support from the New Deal.

In 1935, when the right-wing Supreme Court ruled the NIRA unconstitutional, Roosevelt moved for greater empowerment of workers. In fact, it was only when the NIRA was shut down that FDR moved toward the greater empowerment of workers.

He was originally skeptical of the act because it did so much for workers and seemed anti-business. But the election of 1934 created an overwhelming liberal Congress that the political space existed for Roosevelt to take such a significant step.

Senator Robert Wagner (D-NY) shepherded the bill through Congress (and giving it its popular name of the Wagner Act). Wagner had long been a champion of labor.

He had served as chairman of the New York State Factory Inspection Commission in the aftermath of the Triangle Fire and built upon that to become a Democratic senator from the state in 1927.

Wagner was the Senate’s leading liberal during the New Deal, shepherding a variety of legislation through the body, particularly around labor issues.

The NLRA guaranteed “the right to self-organization, to form, or assist labor organizations, to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing, and to engage in concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid and protection.”

The law applied to all workers involved in interstate commerce except those working for government, railroads, airlines, and agriculture.

The agricultural exception, as in the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, continues to lead to the exploitation of agricultural workers today, but agricultural workers meant these laws would have failed in Southern opposition.

All change in this nation’s history — all of it — has been incremental.

The most important part of the NLRA was the establishment of the National Labor Relations Board, creating a government agency with real authority to oversee the nation’s labor relations.

The government had now officially declared its neutrality in labor relations, seeing its role as mediating them rather than openly siding with employers to crush unions.

This was a remarkable turnaround in a nation where union-busting was a good political move for the ambitious pol. After all, Calvin Coolidge, out of office only four years before Roosevelt took over, made his name by busting the 1919 Boston police strike.

Businesses went ballistic after the NLRA passed. Business Week ran an editorial titled “NO OBEDIENCE!” It read: “Although the Wagner Labor Relations Act has been passed by Congress and signed by the President, it is not yet law. For nothing is law that is not constitutional.”

Conservatives immediately challenged the constitutionality of the NLRA. But Roosevelt’s war on the Supreme Court, while damaging his prestige and ability to get new legislation passed, did have an effect.

The pressure of a changing nation by the time the case came to them had an effect. In the 1937 decision in NLRB v. Jones and Laughlin Steel Corporation, the court ruled 5-4 in favor of the government and the act’s future was ensured.

Within a year of the decision, three justices retired and Roosevelt ensured the future of his programs.

It’s also important to remember what life for workers was like before the National Labor Relations Act. It wasn’t just that they couldn’t form strong unions and thus were poor, although that was a piece of it.

It’s that companies could do basically anything they wanted to in order to stop or bust a union. They could hire spies. They could hire a police force. They could kill union organizers. They could fire you for joining a union.

Corporations had all of the power and workers had none because in the end, the government was willing to back up the companies through legislation or even through military intervention to bust unions. The NLRA ended that, perhaps not entirely, but largely.

Leveling the playing field meant workers now had the right to a decent life, a right they were happy to grasp and to fight for. And fight for they did, as union membership skyrocketed after the NLRA was upheld by the Court.

In other words, social movements require accessing the levers of power, even if that means compromising on key principles, in order to codify change.

As is the case with most legislation, the NLRA proved susceptible to conservative regulatory capture. Today, the NLRB is a shell of its former robust self thanks to Republican attacks on it as one of the few agencies dedicated to giving workers a fair voice on the job, a principle which the Republican Party opposed in 1935 and opposes in 2020.”