Follow Erik Loomis on Twitter

Read Erik Loomis at Lawyers, Guns, & Money

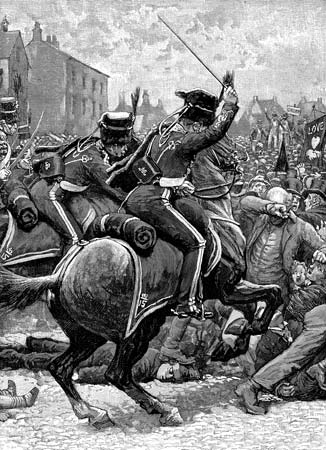

Historian Erik Loomis on This Day in Labor History: August 16, 1819. British cavalry charged into a crowd of workers in Manchester, England who had gathered to demand parliamentary representation and the repeal of laws making food more expensive, killing 15. Let’s talk about the Peterloo Massacre.

This movement of working class radicalism was deeply intertwined with conditions of British workers during the Industrial Revolution and the early manifestations of political radicalism this created.

In the early 19th century, democratic participation was nearly non-existent in Britain. That nation had resisted the move toward democracy spawned out of the American Revolution and French Revolution, even as those nations were also dealing with the implications of it.

Meanwhile, after the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, Britain fell into an economic depression. Unemployment rose and hordes of the new industrial workers lost their jobs and had nowhere to go.

By 1819, industry was deeply affected at the same time that food prices had risen dramatically. The region’s textile mills, the core of the Industrial Revolution, had a brief boom after the war ended, but that quickly collapsed.

Free-market industrialists said there was nothing they could do but lay people off and cut wages. At the same time, they publicly opposed any form of public relief for the urban poor.

Moreover, the British government instituted the first Corn Law, which imposed tariffs on imported grain, creating food shortages and near-famine conditions for the poor, particularly in the aftermath of the legendary 1816 summer that never happened after Mount Tambora exploded.

Economic-based organizing began in 1817 with a movement called the Blanketeers.

They started in Manchester that March, hoping to spawn a march of textile weavers to London to present petitions demanding that the government take steps to improve the cotton trade so they could go back to work.

Magistrates responded by reading the marchers the Riot Act and arresting 27 of them. Organizing for both political and economic reforms continued. Henry Hunt became the leader of this new movement.

Hunt became the most famous popular radical of his day, a sort of Eugene Debs for the early 19th century, promoting broad-based political and economic reforms.

He argued for universal male suffrage and Parliament held every year, without the rotten boroughs that ensured the government stayed in the hands of conservatives.

He was a big believer in mass rallies, believing that if large enough crowds gathered, it would place pressure on the government to transform without having to engage in bloody insurrection.

For the British elite, these combined political and economic protests meant Jacobinism had crossed the Channel. Hunt began leading mass rallies in Manchester. In January 1819, one rally attracted 10,000 people.

Manchester’s leaders wrote to London, fearing a general insurrection and complaining of their lack of power to shut down the rallies or repress the press reporting on these conditions and encouraging action

When Hunt decided to lead a mass rally on August 9 in St. Peter’s Fields in Manchester, the police attempted to intervene. Declaring it illegal preemptively, Hunt and the other leaders delayed it for a week, but were determined to hold the meeting.

When that rally achieved an unprecedented crowd of 60,000, the police acted. As far as is known, the 60,000 protestors were completely unarmed, as Hunt and others hoped to preempt intervention by banning weapons.

They also encouraged workers to wear their Sunday best clothing to present an atmosphere of respectability. Groups carried banners with slogans such as “No Corn Laws” and “Vote by Ballot.”

There was no violence from the marchers reported. The magistrates however ordered the speakers arrested. The yeomanry ordered to arrest the speakers were untrained and they panicked.

Moreover, the head of the British army in the area figured that not much would happen at the rally and instead decided to go see his horses race nearby. But instead of arresting the speakers, they unsheathed their swords and charged into the crowd.

The magistrates then ordered the 15th Hussars and Cheshire Volunteers to assist and a general bloodbath ensued. The Hussars especially were just seeking to kill as many people as they could.

It’s surprising that only 15 or so people were killed, especially given the injury totals of probably over 500. Among the dead were Mary Heys, a pregnant mother of six run down by the charging horses, causing the baby to begin birthing. She died in childbirth.

Sarah Jones, a mother of seven, was killed by being beaten in the head. John Ashton was one of the movement’s political leaders who carried a banner reading “Taxation without representation is unjust and tyrannical. NO CORN LAWS.” He was sabred and then trampled.

Many of the wounded actually hid their injuries in order to escape arrest and prosecution. Riots then occurred in Manchester and nearby towns for the rest of the day, but all the violence ended a few days later, although one constable was killed by a mob on August 18.

The British government responded by cracking down on the political reform. It expressed its support for the massacre. Conservatives feared uprisings around the country. It passed the Six Acts that clamped down on public meetings, newspaper opposition, and gun ownership.

Hunt was not hurt in the protest although his hat was stabbed through. In 1820, Hunt was convicted on a charge of sedition for his radical views and spent two years in prison. While there, he wrote a book exposing the horrible conditions of the prison.

Eventually, Hunt’s movement and the sacrifice of the dead at Peterloo led to the parliamentary reforms of 1832. It would take much more than that to fix the poverty of the British working class.

The Corn Laws were not eliminated until 1846, when the Irish famine managed to convince enough lawmakers that they should do something to alleviate it that they once again allowed for cheap imported grain. Conservatives were, of course, outraged.