Follow Erik Loomis on Twitter

Read Erik Loomis on Lawyers, Guns, & Money

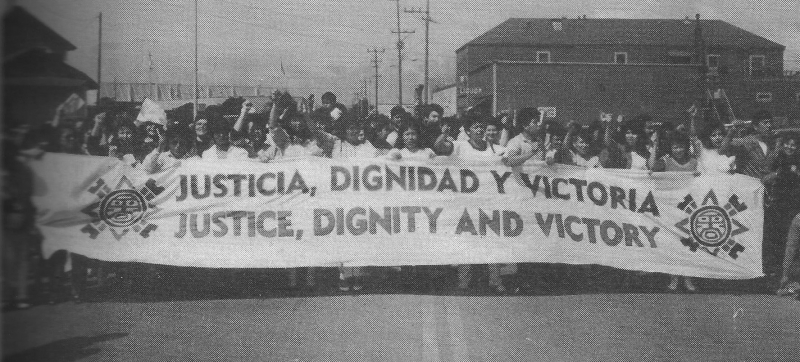

Historian Erik Loomis on This Day in Labor History: September 9, 1985. The Latina workforce in the large frozen food facilities in Watsonville, California walked out on strike after employers cut their wages. Let’s talk about this hard fought win for people who are the future of the labor movement.

The food processing industry has long been a race to the bottom. It’s a fairly low capital industry that allows capitalists to open new factories wherever they want.

Moreover, since this is canned and frozen food, the same immediacy that gave farmworkers their power was not as stark here. By the 1980s, the age of capital mobility was in full swing and lots of our processed foods were coming from Mexico.

Moreover, many of the rest of these factories were in the South. These were largely low-wage and pretty exploitative factories.

The cannery workers in California had won union contracts with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. And while the Teamsters often get a bad reputation in these years, it could be a great union that did a great job of fighting for its members.

In fact, these factories had been unionized since all the way back in 1949, when one employer signed a contract with the Teamsters, creating an industry-wide wage pattern. But by 1985, the employers had no interest in continuing this relationship.

The largest of them, Watsonville Canning, decided to force the workers on strike in order to find an excuse to close the plant and then reopen it without organized labor and with much lower wages and far more limited benefits.

And it’s not as if the union was particularly ready for this. IBT Local 912 was run by a guy named Richard King, who may have represented Spanish-speaking workers but who did not speak a word of it himself.

Like many union leaders — both at the international and local level — by the 1980s King felt he had such a good personal relationship with the employers that he really didn’t need to organize the workers.

So when the employers decided to change the equation, King found his response as flatfooted as that of AFL-CIO president Lane Kirkland.

For the Teamsters — seeing what was happening around the country — this was a battle with great meaning. The 1980s was a horrible decade for the labor movement. Critical struggles were lost all the time.

That began with Reagan firing the air traffic controllers, but also included Phelps-Dodge busting its unions in Arizona and the legendary P-9 strike in the Austin, Minnesota meat packing plant memorialized in Barbara Kopple’s American Dream.

The IBT could read the writing on the wall and worried about the future of the entire union, not just these workers.

Only about 15 percent of the workers in the plant were women, but they became the strike leaders. Some came from militant backgrounds in Mexico, though few had been on strike.

Immediately, the town powers tried to come down on the side of the employer, as the farm communities of California had always done when faced with labor struggles. A local judge issued an injunction against picketing within twenty-four hours.

It was so restrictive that one worker was arrested for picketing while doing so on her own front porch. The city council and mayor refused to allow Spanish translation of the meetings so the workers could know what was happening.

And it was tough. These were poor people. A lot of people lost their homes. Some returned to Mexico.

At first, the IBT didn’t provide much leadership. Workers had to figure out how to run a strike as they went along.

But the IBT then sent a Spanish speaking organizer named Alex Ybarrolaza to run the local and he was very good, building trust between workers and the union and providing the necessary professional expertise to run a big strike like this.

The employer believed they would cave within a couple of weeks and come begging for their jobs. He was wrong. In fact, he was so wrong that his own personal fortune began to dwindle. Unwilling to settle and facing bankruptcy, he ended up selling the plant.

He had hired scabs, but the workers managed to harass them to a significant extent, enough to discourage them. Moreover, conditions inside the plant were terrible. Many of the scabs soon quit and there was so much turnover that the place stopped being profitable.

The Teamsters’ gigantic bank account helped. Because the products of the factory were sold under different names, a direct boycott wasn’t feasible. But Wells Fargo was bankrolling the owner with a large line of credit.

And the Teamsters had over $1 billion invested in Wells Fargo-run pension accounts. That was a major tool.

When the IBT threatened to pull its pensions out of the bank if it continued extending credit to the increasingly in debt owner, Wells Fargo responded. A billion is a lot of money. The bank cut the plant off. Bankruptcy soon was inevitable.

The plant was sold in early 1987 to a local broccoli farmer who the factory hadn’t paid for $5 million worth of it when the strike started. So he certainly had no love for the guy who caused all these problems. Five days later, the new owner came to an agreement with the IBT.

At first, this did not work. Because it was a new company, technically, the contract had a three-year window before medical care would kick in. These workers had already been without insurance for 18 months. So they protested against their union.

After a few days of direct action, the Teamsters realized they needed to figure it out and came to a new agreement with the owner that fixed most of the health care issues.

And it was a major victory for the workers in that it basically reinstated everything to the same as the rest of the contracts in the area.

After the strike, United Farm Workers head Cesar Chavez summed up what the Watsonville workers had won. He said, “When they went out on strike, they were totally disorganized. There was no rank and file leadership. But when they went back in there was strong leadership and a real union. These women in Watsonville have set a precedent. More than the wages, more than the money, is that they broke that long, long period of no strikes and no fight-back.”

This was accurate but rich coming from Chavez given that by the late 1980s he ran the UFW as a cult of personality and allowed absolutely no local leadership. But he was still right on Watsonville.

Unfortunately — as was the case for many union victories in these years — the glorious achievements were short-lived, as capital mobility did not stop and most of these unionized workplaces in Watsonville closed down within a few years.

If you want to read more on Watsonville, check out Peter Shapiro’s Song of the Stubborn One Thousand: The Watsonville Canning Strike, 1985-87.